One of the most common arguments put forward by the Catalan pro-independence movement is that Spain is essentially impossible to reform. According to those who argue this, given the political and institutional equilibrium in the country, and given that Catalonia is a permanent minority within Spain, it will never have the strength or sufficient weight to force the central government to accommodate its demands for self-government. Hence, unilateral secession is the only way out. Moreover, so the argument goes, this fact will not change substantially after the next general election since, no party will be able to make an offer that would attract the more pragmatic sectors within the secessionist bloc.

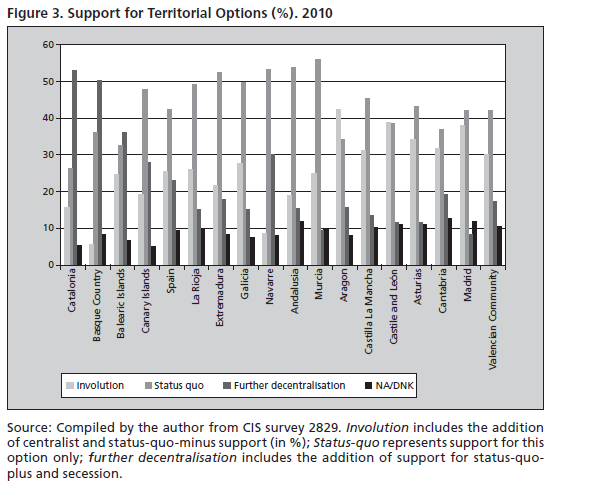

The idea is simple. While citizens at some regions want to increase their self-government or even get to independence (Catalonia), others at different areas follow the opposite way, actually wanting to ‘return’ powers to the central government. From this point of view, it looks like the aforementioned argument does exist and that there is a very limited margin for any territorial reform in Spain. Statewide parties will keep the position preferred by their voters, and Catalans will do the same. However, I believe that there are two good reasons to think that this is less of a barrier than what might look like.

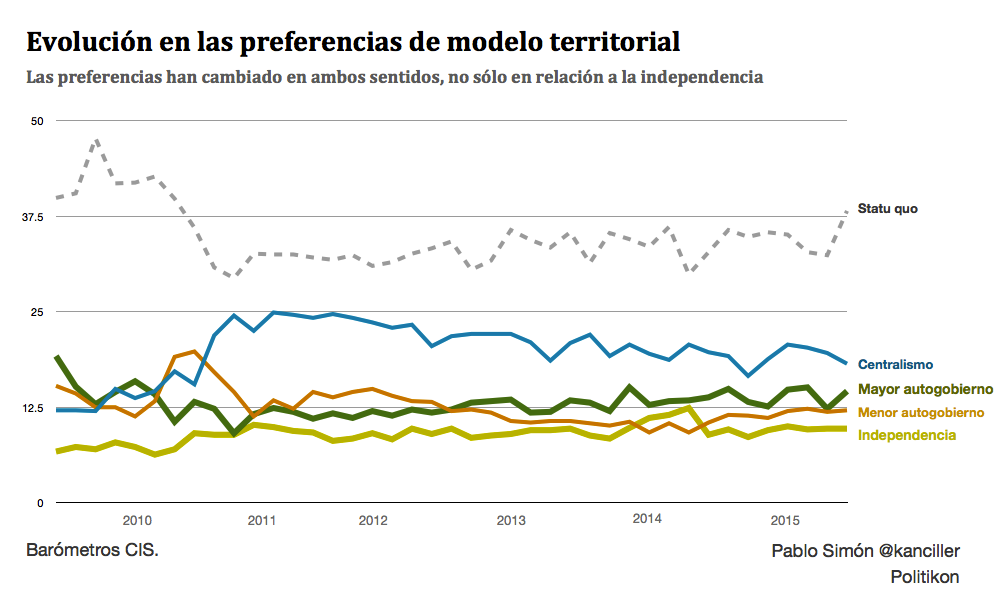

First and foremost, it is assumed that those preferences are fixed, something that does not seem to make a lot of sense. If support to independence has changed, why wouldn’t other options change as well? If we look at the whole picture it is easy to confirm the change in the model of territorial organization asked by Spaniards according to the CIS.

What exists is an almost-perfect correlation between the most crude moments of the economic crisis (and the access of the PP to the government) with a larger preference for re-centralization. Those were the times of hearing arguments of «closing regional TV stations and embassies» to end with the crisis, coming from specific parties and media. Those were the times of regional governments declaring bankruptcy. Back then, crude arguments were dominant: the crisis seemed to multiply the opportunity cost of decentralization. With hard consolidation policies going on, regions were seen as a luxury or, even worse, as a shelter for lazy politicians.

The crisis has spurred Catalonia and the rest of Spain in opposite directions regarding who bears with organizational responsibility for our misfortunes. In Catalonia, it goes against Spain. In Spain, it goes against the regions. However, the current trend seems to show some reflux regarding re-centralization. It is possible that the recoil of discontent towards the political supply has had an impact — reducing the widespread rejection towards parties and institutions. An apparent economic improvement might have played a role as well. Or maybe everyone has suddenly become federalist. Whatever the reason, what data shows is that these preferences can change in both directions. And this is something crucial.

But there is a second argument. In my opinion an eventual support to greater self-government among Spaniards is neither necessary nor sufficient condition for a reform to increase decentralization. It is not a necessary condition because if one thinks about how the current regional division began, the absence of a spirit of self-government in most regions is obvious – identities were built later on. Moreover, considering the second-generation reforms of regional charters [‘Estatutos’, regional constitutions], the preference of the majority was for the status quo in all cases, i.e., a rather neutral position. And I do nor consider the condition to be sufficient because at the end of the day it is the positions of regional elites that define the process of self-government.

The reason for that is that most people outside the historical regions (Catalonia, Galicia, Basque Country, Navarra, etc) have a very limited interest for the territorial issue. Whenever a given topic does not appear to be too relevant, preference formation is usually conditioned by either parties’ position or by polarisation. For instance, it can be considered that the degree of attack to self-government from the Constitutional Court is equivalent in the two following cases: when the co-payment system was invalidated for Catalonia, and when the Andalusian anti-eviction law was halted. But only the first case was considered as a direct, intolerable attack, whereas in Andalusia it was seen as mere partisan attack [the region is governed by the socialists].

All this makes a reform scenario much more viable than what the pro-secession camp seems to be signalling. From my point of view neither preferences are fixed nor these are as relevant as they seem. However, it would be too optimistic, voluntaristic to assume that the agreement will be easy. Probably, the main problem ahead will not be the opinion of, say, the people from Murcia on the current territorial structure of Spain. The challenge is the weakness of classic statewide parties in Catalonia, and their organisational tendency to rely on more conservative regional branches. In any case, we should wait to see what is the final seats contribution of Catalonia for those parties who have arrived more recently, and check its balance. Even more importantly, we will have to find out whether it is possible or not to put on the table a reform proposal that is attractive enough to get on board all those Catalans (and even Spaniards) who really think that this country is impossible to reform.

***

On a side note

Few among us like the current status quo. As a matter of fact, in past Catalan elections only 11 out of 135 MPs are in favor of it. However, we should not forget that the current territorial model is son of many parents. Nobody casts doubt on the responsibility of the two main traditional parties. But let’s not forget that half of the national governments over time have been supported by Catalan parties. Some of those who today sound particularly tragic when talking about the lack of possibilities to reform Spain are at the very least partially responsible of the current situation. And nobody seems to be questioning them.

[…] desde hoy Politikon tendrá también artículos en inglés. Los hay (y habrá) de varios tipos: algunos son traducciones de textos previamente publicados que nos parecen particularmente interesantes para […]