No one doubts the importance of the upcoming Catalan elections. Several things make them rather special: First, the pro-independence camp has insisted on their plebiscitary character; second, there’s at least three new parties or coalitions – Junts pel Si, Catalunya sí que es pot, and Unió (and also a change in every single leadership except for the curious case of Mas, the incumbent president, who is running but not leading his own ticket); and third, their proximity to the Spanish general elections.

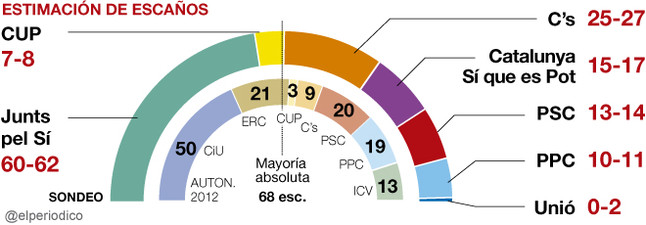

The first polls – to read Lluis Orriols’s analysis, click here – are mostly in agreement; Junts pel Si and CUP may attain (or at least get very close to) a majority of seats in the Parliament. Although I would not take for granted CUP’s support to reelect Mas, in any case there would be a separatist government in Catalonia with a clear roadmap towards secession.

A key element to understand this early lead in the polls is that mobilization in the separatist camp is clearly superior to that of the «unionists.» In political science there’s been much talk of the differential abstentionist, the Catalan who only votes in the general elections but doesn’t show up for the Catalan elections. However, in the 2012 Catalan elections this changed, as participation rose higher than it had been for the general elections. We must then be cautious, because polarization can lead to higher turnouts. It is also possible that the mobilization of the “unionist” camp will happen later on in the campaign, which unsurprisingly started on September 11 (Catalan National Day); the elections themselves are on the feast of la Mercè (a holiday in Barcelona), which might catch a fraction of locals (traditionally more unionist) away from their city.

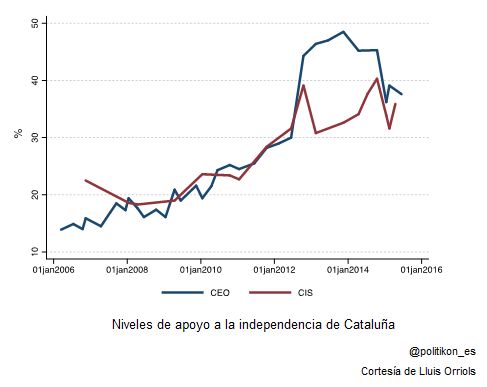

This mobilization and strength of the pro-independence camp, which could attain a majority in Parliament, is also somewhat paradoxical. As indicated by both the CEO and the CIS, support for independence in Catalonia has fallen significantly in the past few months. This could point to some interesting clues.

It is often said that independence is a question of identity, with a strong ethnic component. And indeed, identifying oneself in polls as «Spanish only» or «Catalan only» is a good predictor of the vote in a possible independence referendum. However, we have not seen a major transformation of identity in the last decade and most people remain under the mixed options. Therefore a change in the sense of national belonging does not seem to be (primarily) behind the rise of independence since 2006 (and more recently, its fall). It seems rather that there are political reasons that explain the movements.

If we look at the time series, support for independence begins to grow with the economic crisis, which started somewhat before the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the Catalan self-rule statute. The latter acts as a focal point because of its symbolic value. Of course, the substantive material of the ruling itself is relatively unimportant (but this is a whole different issue), and what matters is the fact that the Catalan political actors considered it a breach of a covenant and thereafter steered in their positions. In any case, although all of these factors are relevant, the main kick-starter for the pro-independence surge is the Popular Party’s accession to power and the harshest budget adjustments. That’s the peak of pro-independence sentiment, which plays a curious parallel with Scottish independence and the Tory government.

Now that support for independence is dropping, it might be because some of these factors are (or could be) in retreat. The emergence of new political actors has probably disabled part of the discourse that Spain cannot be reformed. It is not by chance that Podemos garners the most support in Catalonia in general election polls (and it’s not by chance either that the pro-independence camp insists that Podemos is the same as PP and PSOE with regards to the identity cleavage). Maybe the fact that the worst of the crisis is over has marginally reduced Catalan political dissatisfaction. Maybe even the possibility that the Popular Party could lose the government in the next elections is playing a role.

In my view this change in preferences could mean that the window of opportunity for independence may be closing of independence. Of course this is only a hypothesis, but there may be some merit to it.

Undoubtedly there is a significant fraction of Catalans that is pro-independence, regardless of economic arguments or EU membership, and will stick to their views. However, the key actors who can make a difference in terms of political majorities are «instrumental» pro-independence supporter. This is the 10-20% of Catalans who support independence as a bid to change the status quo in Spain. Some of these voters fall close to Convergencia whereas others hail from the catalanist sector of the PSC and changed their preferences in 2010 after the failure of the statutory process. It is a potentially volatile group of voters.

Suppose there are new political majorities in 2016 and a more fragmented Spanish parliament. The result would be the opening of a constitutional reform process – which, regardless of content, is currently supported by all parties except PP. This of course doesn’t mean that all parties will be willing to make an offer to Catalonia; they simply believe the current contract should be reformed.

In this situation, the Catalan political actors will find it difficult to justify not showing up to negotiate. The calculation is that they can choose to get involved to try to get an immediate benefit through a potential reform, or just keep waiting for a future benefit in the form of a unilateral independence (always more difficult than a constitutional reform). In parallel, the cost of continuing the process will continue to rise. Up until now it’s almost all been opportunity costs, but if there is a more serious challenge to the central government by a pro-independence government, it will necessarily be a net loss (even if it is bilateral, as some argue). The combination of both elements can make the «instrumental» voters withdraw their support for independence.

This hypothesis is formulated beyond the result of the Catalan elections. Whether there’s a Junts pel Si government or elections are repeated, soon there will be new majorities in the Spanish parliament – that’s why it was essential that the elections happened now. For the pro-independence camp it’s key to form a government now, since they would much rather have their mandate reflect current preferences than those that might emerge in 2016. In addition, being in office means having access to ways of trying to alter the cost structure of or derail the constitutional reform (they won’t lack political allies in Madrid for this purpose).

We all know that the incentives to negotiate so far have been scarce. In the short term both the pro-independence camp and the central government have an interest in polarizing the debate to improve their electoral prospects, one in Catalonia and the other in the general elections. CDC has already tied its fate to the independence process for better (to save its own brand and officials) and for worse (losing political control of the situation). Meanwhile, the PP has waited to see if the contradictions within the movement would manage to deflate it. After last year’s failed referendum it seemed that this strategy had succeeded, but the joint pro-independence list has told us otherwise.

The question is who will negotiate from now on, since many traditional actors have fallen victims of attrition. To this I have no answer. Neither the Catalan nationalists will be as decisive as they were in the minority governments of both PP and PSOE; neither the former CiU nor the PSC have the centrality of Catalan society that they had in the past. We will continue moving on uncertain ground until we see the new balance of forces.

However, precisely because many Catalans have seen independence as the only way to change the status quo, a real possibility for reform might be all that can change their views. This reform path will be complex, but both the political defeat of the secessionist camp or the entrenchment and continuation of the conflict are dependent on it.

***

Final note:

There are two particularly grueling accounts of all this. On the one side there are those who say that the independence camp is the result of a group of powerful Catalan elites who manipulate society. On the other we have those who speak about a vibrant civil society mobilized for the freedom of an oppressed people. Reality is more nuanced than either. Neither the parties are independent of their members and voter preferences nor ideas arise in a vacuum. This should be taken into account if one wants to understand the situation. If one’s in the business of selling electoral ammunition, then that’s a different story.